In a medical milestone, researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Emory School of Medicine in Atlanta have successfully performed a coronary artery bypass — normally an open-heart procedure — without cutting the chest wall.

The breakthrough offers a potential less-traumatic alternative for patients at risk of life-threatening coronary artery blockage during heart-valve replacement.

“Achieving this required some out-of-the-box thinking but I believe we developed a highly practical solution,” said Christopher Bruce, MBChB, an interventional cardiologist at WellSpan York Hospital and NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), as well as an adjunct assistant professor of cardiology at Emory School of Medicine.

The patient, a 67-year-old man, had previously received a bioprosthetic aortic valve that now needed replacing due to calcium buildup. His unique anatomy placed the opening of his left coronary artery so close to the valve that standard replacement would likely have blocked its blood flow.

“Our patient had an extensive history of prior interventions, vascular disease, and other confounders, which meant that open-heart surgery was completely off the table. Having a minimally invasive alternative in a case like this is paramount,” said Adam Greenbaum, a senior author of the study and physician at Emory School of Medicine.

Existing minimally invasive solutions were also unsuitable. But Greenbaum and Vasilis Babliaros at Emory had begun developing a method tailored to this scenario. "We thought, ‘why don’t we just move the ostium of the coronary artery out of the danger zone?’” Greenbaum said.

Bruce and Robert Lederman, head of the Laboratory of Cardiovascular Intervention at NHLBI, joined the team to translate the concept into a viable procedure, having first tested it successfully in animals.

The new technique, called ventriculo-coronary transcatheter outward navigation and re-entry (VECTOR), reroutes blood flow safely away from the aortic valve. Rather than cracking open the chest, doctors navigate through blood vessels in the legs to reach the heart.

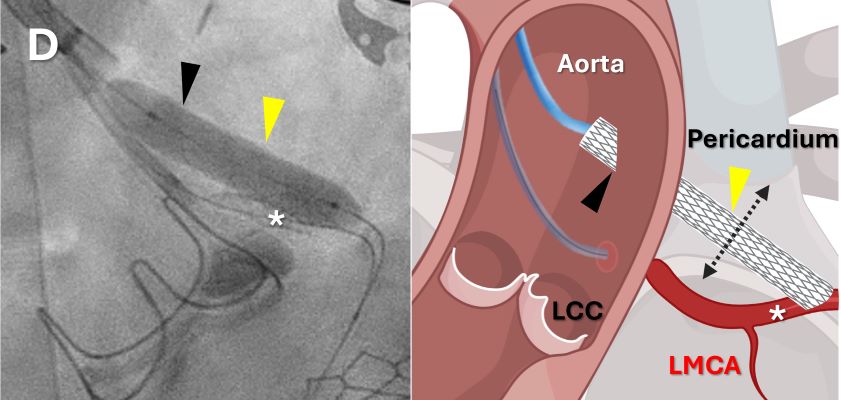

VECTOR involves threading a wire from the aorta into the at-risk coronary artery, steering it through a branch and into the right ventricle. A second catheter grabs the wire, pulling it through the femoral vein, creating a continuous line that allows advanced tools to reach the artery.

The procedure then creates a new ostium for the bypass, using a stent-braced catheter to pierce the coronary artery and aorta walls. Two loose ends of a wire are tied to form a bridge, and a bypass graft is fed through, establishing a safe new path for blood flow.

Greenbaum, Babaliaros, and Bruce performed the procedure on the patient. Six months later, he showed no signs of coronary artery obstruction — a first-in-human success for VECTOR.

The team hopes to expand the technique to more patients and believes it could also help treat other coronary conditions where traditional stents fail.

“It was incredibly gratifying to see this project worked through, from concept to animal work to clinical translation, and rather quickly too. There aren’t many other places in the world that can move as quickly and successfully as we can at NIH in collaboration with our partners at Emory,” Bruce said.